In the modern UAP debate, phrases that feel routine today; careful methodology, insistence on instrument quality, preference for negative over ambiguous results, dismissal of witness testimony without multi-sensor data, have clear antecedents.

Much of that intellectual grammar flows from Edward Uhler Condon and the University of Colorado study he led in 1966–1968, formally titled The Scientific Study of Unidentified Flying Objects and commonly called the Condon Report.

Its headline claim that study of the subject was unlikely to advance science was picked up across government and academia and used to justify winding down official inquiries. That decision path still shapes the playing field for UAP research. (NCAS Files)

This article traces how Condon’s personal authority as a physicist, the institutional scaffolding around the Colorado project, and a highly charged internal memorandum created a durable architecture of skepticism. The goal is not to rehearse old fights but to inspect the record and data that made Condon’s influence decisive.

The Physicist Behind the Verdict

Edward Uhler Condon was a prodigy of early quantum mechanics. Born in Alamogordo, New Mexico, in 1902, he earned his PhD at Berkeley and published foundational textbooks that trained a generation of physicists, including Quantum Mechanics with Philip M. Morse and The Theory of Atomic Spectra with G. H. Shortley.

He served as director of the National Bureau of Standards after World War II and later held positions at Washington University in St. Louis, Corning, and the University of Colorado. The American Institute of Physics’ historical profile emphasizes his broad scientific portfolio, public service, and the turbulence of the loyalty security controversies he endured during the 1950s.

This background matters because it lent extraordinary credibility to any position he took on UAP. (Niels Bohr Library & Archives)

Condon’s stature meant that the Colorado study could, if it wished, reframe the entire topic for mainstream science. When the Air Force asked the University of Colorado to undertake the investigation, the choice of Condon made the project both plausible to funders and appealing to media. (NCAS Files)

How the Colorado Project was Built

The Colorado team worked under Air Force contract F44620-67-C-0035. The online table of contents shows a sprawling enterprise: conclusions and recommendations, a long summary, a methods section titled The Work of the Colorado Project, fifty nine detailed case studies, historical chapters, and technical chapters on optics, radar, atmospheric electricity, balloons, instrumentation, and statistics. Appendices include the 1953 Robertson Panel report, Air Force regulations governing reporting, early warning network materials, and a letter from Gen. Twining that framed the 1947 policy response. (NCAS Files)

Staff and collaborators were diverse. Formal investigators included Roy Craig, who wrote the Field Studies chapter, and astronomer William K. Hartmann, who performed quantitative photo analyses. The acknowledgments list broad cooperation: NASA liaison Urner Liddell, Air Force officers Robert Hippler and Hector Quintanilla, and advisors such as J. Allen Hynek and Jacques Vallée. Daniel S. Gillmor served as editor. This was not a small team working in isolation; it was embedded in the contemporary scientific and aerospace establishment. (NCAS Files)

The project’s own summary defined the term under study in disarmingly pragmatic terms. A UAP report was treated as a stimulus for a report, a choice of words that explicitly decoupled the phenomenon from any claim about material craft. That definitional move shaped what the study measured and what it considered out of scope. (NCAS Files)

What the Condon Report Actually Said

Condon’s Section I conclusions and recommendations are the keystone. The most quoted line reads, in essence, that nothing from the past twenty-one years had added to scientific knowledge and that further extensive study probably could not be justified on the expectation that science would be advanced.

He also argued that the federal government should not create a new dedicated program and that Project Blue Book’s defense function could be integrated into routine intelligence and surveillance.

Perhaps most provocatively for those who suspect secrecy, he wrote bluntly that the team found no evidence of secrecy concerning reports. This combination of framing, resource guidance, and cultural messaging hardened scientific caution into institutional posture. (NCAS Files)

The Panel of the National Academy of Sciences reviewed the Colorado report in late 1968 and agreed that the scope had been adequate, the methodology generally acceptable, and the conclusions reasonable. The NAS panel highlighted that of thirty-five photographic cases, none proved to be real objects with high strangeness and that most could be assigned to misinterpretations or fabrications. This imprimatur elevated the Colorado work from a contractor product to a yardstick.

In December 1969 the Secretary of the Air Force cited the Colorado report and the NAS review to announce the termination of Project Blue Book. The press release repeated the three familiar conclusions: no threat to national security, no evidence of advanced technology, and no evidence of extraterrestrial vehicles. The official Air Force fact sheet later summarized the database as 12,618 reports with 701 remaining unidentified. Those numbers are still used as a baseline in historical discussions today.

Inside the Methods the Cases that Still Echo

The Colorado project combined archival review, field investigations of current reports, and specialized analyses. Key examples illuminate both its rigor and its critics’ complaints.

McMinnville photographs, Oregon, 1950

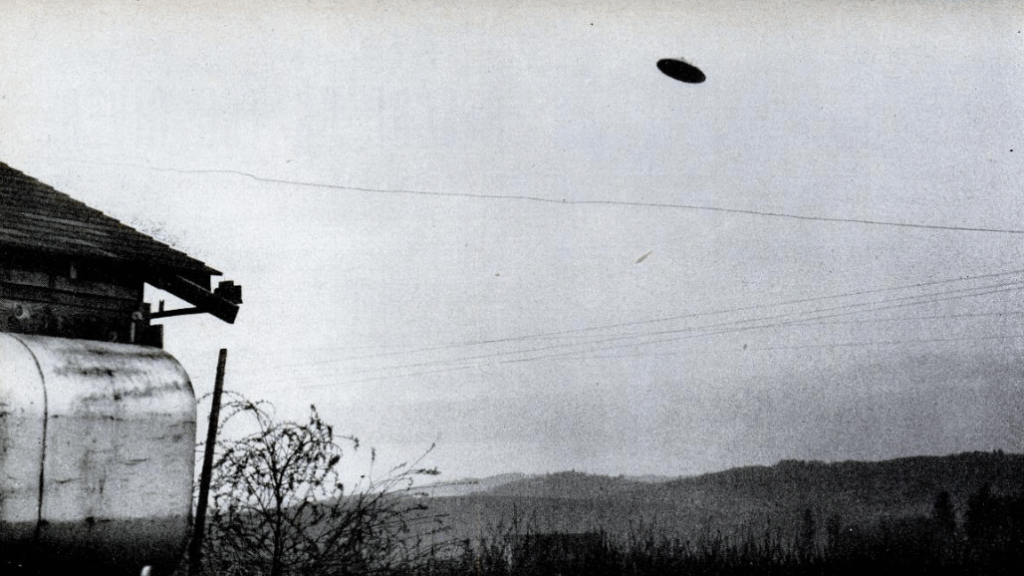

Hartmann’s analysis modelled geometry and photometry. He did not endorse an exotic craft hypothesis, but he acknowledged that the images were not readily explained as a fabrication. Critics later argued that the report’s executive summary downplayed technical ambivalence in favor of a categorical conclusion about scientific futility. Whatever one’s view, the original case chapter is still a master class in method. (NCAS Files)

Great Falls, Montana film, 1950

The team re investigated the filming date, compared witness accounts with base operations data, and weighed airplane reflections versus other hypotheses. The chapter is a vivid demonstration of how small uncertainties in dates cascade into loss of diagnostic power. It also illustrates a pattern that later shaped scientific culture around UAP: when in doubt, prefer the conservative explanation. (NCAS Files)

Numbers and categories

The NAS review tallied fifty nine case studies, with ten predating the project because their documentation was unusually strong. Across photographic cases, the distribution skewed toward insufficient data, misinterpretation, or fabrication. Cases with residual ambiguity rarely drove program level conclusions. That asymmetry became an enduring feature of institutional risk calculus.

The Low Memorandum and a Crisis of Confidence

If the Colorado project was an engine of skepticism, the August 9, 1966 memorandum by Robert J. Low was the fuel for a generation of doubt about whether the engine had been tuned in advance.

The now famous line described a communications strategy in which the project would appear totally objective to the public while sending a different signal to the scientific community that it would be led by nonbelievers with almost zero expectation of finding a saucer.

The memo also suggested emphasis on psychology and sociology of observers rather than physical phenomena. When critics found and circulated the memo in 1967–1968, it became the centerpiece of allegations that the study had been biased from inception. (NICAP)

Science magazine reported the controversy during the project’s final year. Whether the memo reflected Condon’s views is disputed. Some insiders argued that Condon did not know of the memo for many months and that the team’s published case chapters spoke for themselves. Others insisted the memo matched the project’s managerial tone and discouraged instrument forward inquiry. The existence of the memo is plain; what it proves about institutional intent remains a matter of interpretation. (PubMed)

Beyond Colorado how the Conclusion Became Policy

The path from a contractor’s report to federal policy and professional norms was quick. The Air Force’s December 17, 1969 announcement explicitly cited the Colorado report and the NAS review to justify closing Blue Book.

The official fact sheet fixed the record at 12,618 cases, 701 unknowns, and no evidence for advanced technology. Government agencies used those sentences for decades when queried by media and Congress.

In the technical community, the American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics took a nuanced position in 1970. Its Subcommittee on UFOs concluded that the only promising approach would be a continuing, moderate level effort focused on improved objective data collection and careful analysis. It did not simply echo Condon’s call for no further study. This is often overlooked and suggests that even within mainstream aerospace, there was room for carefully bounded research. (UNT Digital Library)

What “scientific skepticism” Meant after Condon

Condon made several linked moves that hardened into a template for skepticism.

- Define the target as a class of reports rather than as physical craft.

That shifts the test for success from discovering physical anomalies to improving error budgets in perception and instrumentation. (NCAS Files)

- Set the burden of proof at a level that ambiguous field data could rarely meet.

The photographic chapter and the NAS review both show how strong that bar became.

- Tie the resource question to national scientific priorities.

By arguing that further extensive study probably would not advance science, Condon provided a principled reason for funding agencies to say no even while acknowledging that targeted proposals might be worth considering case by case. (NCAS Files)

- Normalize the idea that official secrecy was not blocking progress.

Condon wrote that the team found no evidence of secrecy concerning reports. Whether readers agree or not, this assertion gave administrators a talking point that reduced pressure for special handling of the subject. (NCAS Files)

The result was a culture in which ambiguous UAP evidence was handled as noise to be filtered rather than as signal to be amplified. That culture did not end inquiry, but it changed what counted as valuable work.

A Reactive View from Today

Contemporary agencies have returned to the topic with different vocabulary and a data forward posture. NASA’s 2023 UAP Independent Study Team called for rigorous, evidence-based approaches, improved data acquisition, a systematic reporting framework, and reduction of stigma, while emphasizing that NASA’s assets could constrain environmental conditions that coincide with reports.

The study explicitly treats UAP as a topic demanding better data engineering rather than casual dismissal. This is not a repudiation of Condon’s standards, but it is a different operational answer to his resource argument. (NASA Science)

The Defense Department’s All domain Anomaly Resolution Office has similarly emphasized historical record consolidation and sensor driven analysis. In 2024 it released a historical record report with extensive references to earlier programs.

Whether modern analytic capacity that did not exist in 1968 can change outcomes remains an open question. (AARO)

The Condon Report by the Numbers

- Contract and scope: University of Colorado study, 1966–1968, Air Force contract F44620-67-C-0035; fifty nine detailed case studies, with extensive technical chapters and twenty plus appendices. (NCAS Files)

- Definitions: the study treats UAP as the stimulus for a report, explicitly bracketed from ontological claims. (NCAS Files)

- Executive conclusion: further extensive study probably not justified in expectation of scientific advance; no evidence of secrecy concerning reports. (NCAS Files)

NAS review: scope adequate, methodology acceptable, conclusions reasonable; no photographic case proved a real object with high strangeness. - Policy outcome: Project Blue Book terminated December 17, 1969, citing the Colorado report and NAS review; cumulative database 12,618 reports, 701 unknown.

Investigative spotlight was there a cover up or a consensus?

The Low memo is the heart of the cover up claim. Its language about the trick of projecting objectivity to the public while reassuring the scientific community fed the perception that the study’s verdict was foreordained.

Once revealed, the memo triggered staff turmoil, media coverage, and severed relationships with some civilian organizations. Whether that proves intent or only suggests an administrator’s pitch to nervous colleagues is still debated. The documentary record confirms the memo’s content and the ensuing conflict; interpretation remains divided. (NICAP)

Condon’s own text complicates the narrative. He argued for no secrecy in official handling of reports and left the door open for targeted proposals if clearly defined and qualified. Those lines are often omitted in secondary retellings. They show a scientist trying to balance a skeptical reading of the prior record with the principle that good ideas should be evaluated on their merits. The hardest question is whether the project’s culture ever created enough space for such ideas to surface. (NCAS Files)

Implications for Ufology and for Science

Condon’s influence created both a ceiling and a floor.

The ceiling was cultural: after 1969, it became easy for editors, funders, and department chairs to say that the matter had been settled and that scarce resources should go elsewhere.

The floor was methodological: those who persisted often adopted Condon’s emphasis on rigorous documentation, photogrammetry, and error budgeting to make their work legible to skeptical peers. Even critics built on his methodological scaffolding.

One underappreciated implication is the split between negative policy and positive engineering.

The AIAA subcommittee’s 1970 statement did not endorse a moratorium; it called for a continuing, moderate level program with better instrumentation. That is close to NASA’s 2023 framing and today’s calls for open data pipelines and analytic transparency. Condon’s verdict may have paused one era of investigation, but his insistence on technical clarity ultimately seeded the modern push for sensor fusion and metadata rich reporting. (UNT Digital Library)

Bottom Line

Edward Condon’s influence on scientific UAP skepticism rests on three pillars.

First, unmatched personal authority gave his conclusions social weight far beyond the report itself.

Second, the Colorado project created an analytic and editorial machinery that translated messy field data into orderly scientific prose, with ambiguity treated as a reason to stop rather than a signal to look deeper.

Third, the Low memo and the ensuing firing of staff gave critics a ready made narrative of bias that still shadows the report’s reputation.

For today’s community, the lesson is neither to canonize nor to dismiss Condon. It is to recognize how definitions, burdens of proof, and institutional incentives shape outcomes.

NASA’s 2023 recommendations and the AIAA’s cautious 1970 statement both point to a path Condon left open in principle but that was rarely funded in practice: sustained, instrument centered, metadata rich observation programs that can turn high quality anomalies into testable problems.

That is where skepticism earns its keep and where discovery, if there is any to be had, will eventually live. (NASA Science)

References

American Institute of Physics, Niels Bohr Library and Archives biography of Edward U. Condon. (Niels Bohr Library & Archives)

University of Colorado, The Scientific Study of Unidentified Flying Objects, internet edition by NCAS: table of contents, Section I conclusions and recommendations, Section II definition, Section III Chapter 1 Field Studies, case chapters. (NCAS Files)

National Academy of Sciences panel, Review of the University of Colorado Report on Unidentified Flying Objects.

Department of the Air Force press release, December 17, 1969, terminating Project Blue Book.

USAF Fact Sheet 95 03, Unidentified Flying Objects and the Air Force/Project Blue Book.

Robert J. Low memorandum, August 9, 1966, transcript and images. (NICAP)

Science, P. M. Boffey, UFO Project: Trouble on the Ground, 1968. (PubMed)

AIAA Subcommittee on UFOs, statement summarized in Congressional Research Service document that cites Astronautics & Aeronautics, November 1970. (UNT Digital Library)

NASA, 2023 UAP Independent Study Team Final Report and UAP web resource. (NASA Science)

Claims Taxonomy

Verified

• Existence and content of the Condon Report, including Section I conclusions and the project’s definition of the target phenomenon. (NCAS Files)

• NAS panel review in early 1969 and its principal findings regarding scope, methodology, and photographic cases.

• Air Force termination of Project Blue Book on December 17, 1969, citing the Colorado report and NAS review; official fact sheet totals.

Probable

• That the Colorado report significantly shaped the low priority status of UAP research in mainstream US science for decades, through its use as a policy and funding reference point. Evidence includes immediate policy adoption and persistent recitation of its language in official documents.

Disputed

• The degree to which the Low memo proves project bias rather than an administrator’s rhetorical pitch. Documentary facts are clear; the inference about pervasive bias remains contested among historians and participants. (NICAP)

Legend

• Cultural narratives that present Condon as a lone gatekeeper or as part of a monolithic secrecy machine do not match the documented mix of collaborators, outside advisors, and reviewers. The record is more complex, with multiple scientific bodies engaging the study. (NCAS Files)

Misidentification

• The photographic chapter and case work show many instances where UAP reports are re attributed to aircraft, atmospheric effects, balloons, and hoaxes. The NAS review’s breakdown across photographic cases supports this category.

Speculation Labels

Hypothesis

The project’s communications strategy described in the Low memo predisposed investigators to interpret ambiguous evidence conservatively and to emphasize social science over physical inquiry. Evidence: the memo text; Dismissal of two staff after the memo’s circulation; media coverage. What remains speculative is the strength of the memo’s effect on technical judgments at case level. (NICAP)

Witness interpretation

Scientists and staff who engaged with the project at the time reported different experiences. Some thought the internal tone was dismissive from the start; others reported little direct influence on field work. These are first person interpretations rather than testable claims.

Researcher opinion

The most durable part of Condon’s legacy is not his conclusion but his framing. Defining the problem as reports rather than events makes it very difficult, absent new instrumentation and standardized metadata, for any field investigation program to meet the burden of proof. This framing choice explains far more of the next fifty years than any single case outcome.

SEO keywords

Edward Condon UAP skepticism, Condon Report analysis, University of Colorado UAP study, National Academy of Sciences UAP review, Project Blue Book closure, Robert Low memo, William K. Hartmann McMinnville photos, Roy Craig field studies, NASA UAP Independent Study Team, AIAA UFO Subcommittee statement, UAP methodology, UAP history investigative article, UAP claims taxonomy, UAP cover up debate, UAP data first approach.