From the late fifteenth to the early seventeenth century, Europeans lived under skies that were both intensely watched and richly narrated. The period’s new media ecosystem of broadsheets, pamphlets, and illustrated chronicles multiplied reports of prodigies above towns and fields, while seafarers and travelers transmitted oral descriptions that were quickly copied into journals and printed books. This article maps the most important Renaissance era sources on luminous and structured phenomena in the sky and compares their descriptive language and motifs with features emphasized in modern Unidentified Anomalous Phenomena research. Case studies include the 1492 Ensisheim meteorite and its instant textual afterlife, the Nuremberg broadsheet of 1561 and the Basel broadsheet of 1566, the Stockholm sun dog painting of 1535, striking low latitude aurorae recorded in March 1582, and sailor accounts of St. Elmo’s fire. We situate these within the rapidly evolving scientific practice of the era, especially cometary and nova observations that transformed cosmology. The comparison with modern UAP profiles focuses on recurrent behaviors and visual structures, while the counterpoint sections draw on atmospheric optics, electrical phenomena, print culture incentives, and rhetorical frames of portents. The conclusion proposes a method to digitize and behavior code early modern sky narratives for rigorous cross comparison with modern sensor led UAP baselines. (Astrophysics Data System)

Why Renaissance Europe matters for UAP studies

Renaissance Europe generated a new kind of sky archive. The press produced single sheet broadsheets and pamphlets that reported current events with woodcuts and short explanatory texts, often copied from oral testimony and letters. In the Swiss world this material survives in the Wickiana, a vast dossier collected by the Zurich cleric Johann Jakob Wick and now held by the Zentralbibliothek Zürich. These ephemeral prints documented comets, halos, meteors, eclipses, and many signs that contemporaries read as warnings or wonders. They are among the earliest mass media sources for how ordinary people described the sky. (Zentralbibliothek Zürich)

At the same time, the period produced careful observers who challenged old cosmology. Tycho Brahe’s accounts of the new star of 1572 and the great comet of 1577 argued that change could occur beyond the lunar sphere. These treatises and their images, preserved in early printed editions and modern digitizations, provide a control group of disciplined observation with measurements and positions. They anchor any comparison with looser prodigy narratives. (Causa Scientia)

For today’s UAP analysis, the value of this corpus is twofold. First, it greatly enlarges the time depth of descriptive data about luminous appearances and structured forms in the sky. Second, it demonstrates how genre and media incentives shape what witnesses emphasize, a caution that is just as relevant to smartphone era virality as it was to sixteenth century pamphleteering. (Swiss History Blog)

Case files from the era

The Ensisheim fall of 1492: from sky to stone to print

On 7 November 1492, a large meteorite fell near Ensisheim in Alsace. The event was physically verifiable and rapidly textualized. Poet and humanist Sebastian Brant produced German and Latin broadsheets within weeks, and chronicles across Europe recorded the fall. Modern scholarship has recovered contemporary descriptions and analyzed their circulation. The Ensisheim stone itself was preserved and displayed, embodying a pathway from luminous sky event to durable terrestrial artifact and then to popular print. (Astrophysics Data System)

Comparative note. At one stroke, Ensisheim shows how fast a spectacular sky event could enter a shared textual space in Renaissance Europe, and how quickly explanatory frames competed. The material evidence fixed the category as a meteorite, but the narrative uptake still framed it as a sign. In modern UAP work, official baselines likewise insist on data quality first and caution against over interpretation. Ensisheim is a model of how to treat a striking case without abandoning disciplined identification. (NASA Science)

Nuremberg 1561: shapes and swarms in a sunrise scene

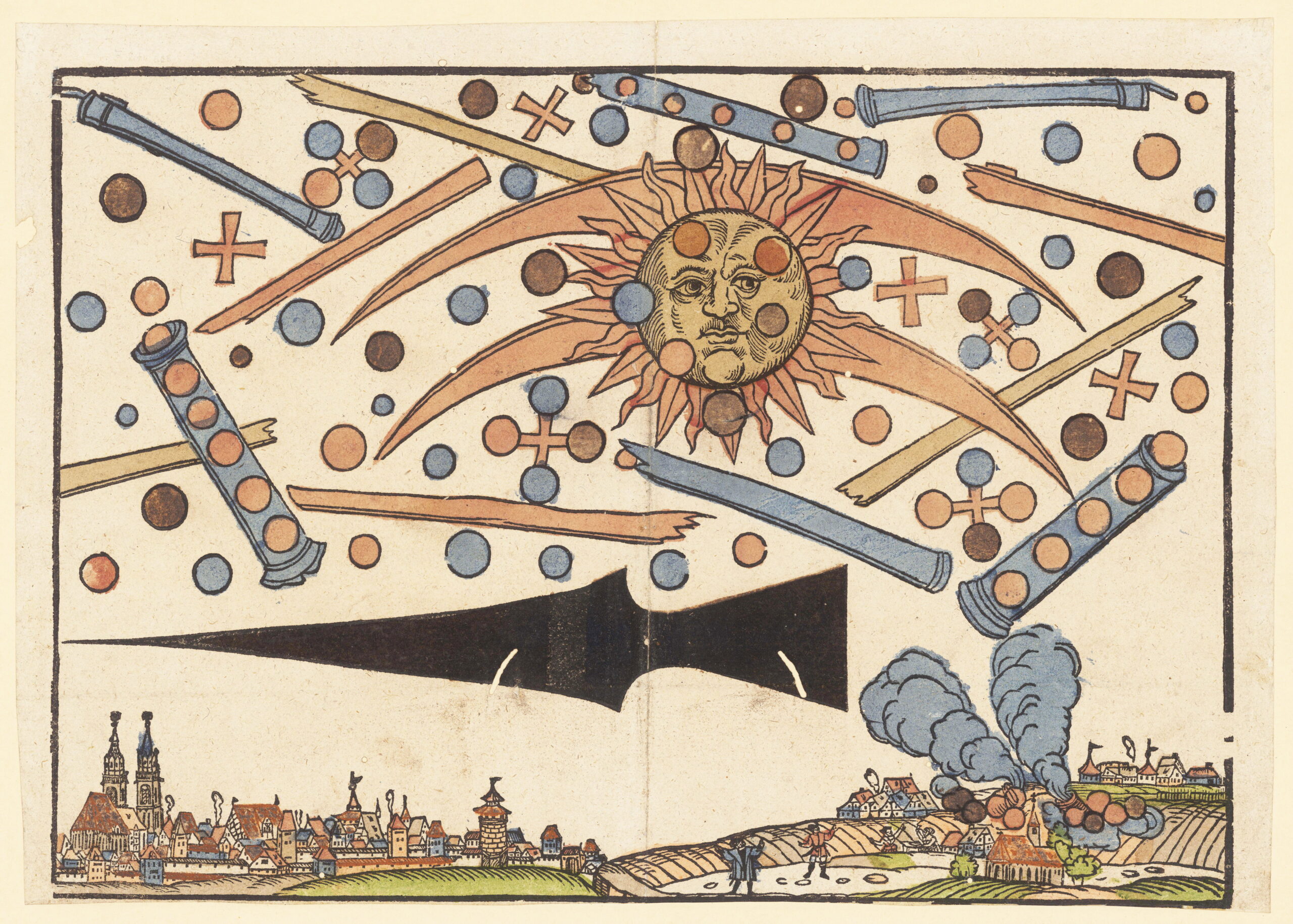

A famous broadsheet by the printer and artist Hans Glaser reported that at dawn on 14 April 1561, many in Nuremberg saw a spectacle “out of the sun.” The woodcut shows spheres, rods, crosses, crescents, and a large dark spear or arrow. The text narrates movements, collisions, and the fall of exhausted spheres beyond the city. The sheet, now preserved at the Zentralbibliothek Zürich, has repeatedly been cited in modern discussions of UAP because of its multiplicity of shapes and its dramatic motion language.

Scholars and science communicators have proposed natural explanations rooted in atmospheric optics. Halo complexes that include parhelia, parhelic circles, pillars, and mock suns can produce brilliant, symmetric, and mobile looking features when the sun is low. Because these phenomena are strongest near sunrise and sunset, they match the broadsheet’s timing and its insistence that the display emerged “out of the sun.” The difficulty is that stylized woodcuts and moralizing text do not report angular distances or color gradations that would let us test a precise optical model. (Encyclopedia Britannica)

Comparative note. The Nuremberg broadsheets’ vocabulary of spheres and rods overlaps with common shape descriptors in modern UAP testimony, and the narrative of clustering and dispersal echoes modern reports of lights that split and re aggregate. Yet the likely optical context and the iconographic program warn against reading the sheet as a technical report. It belongs to a genre that encouraged emblematic forms and moral conclusions.

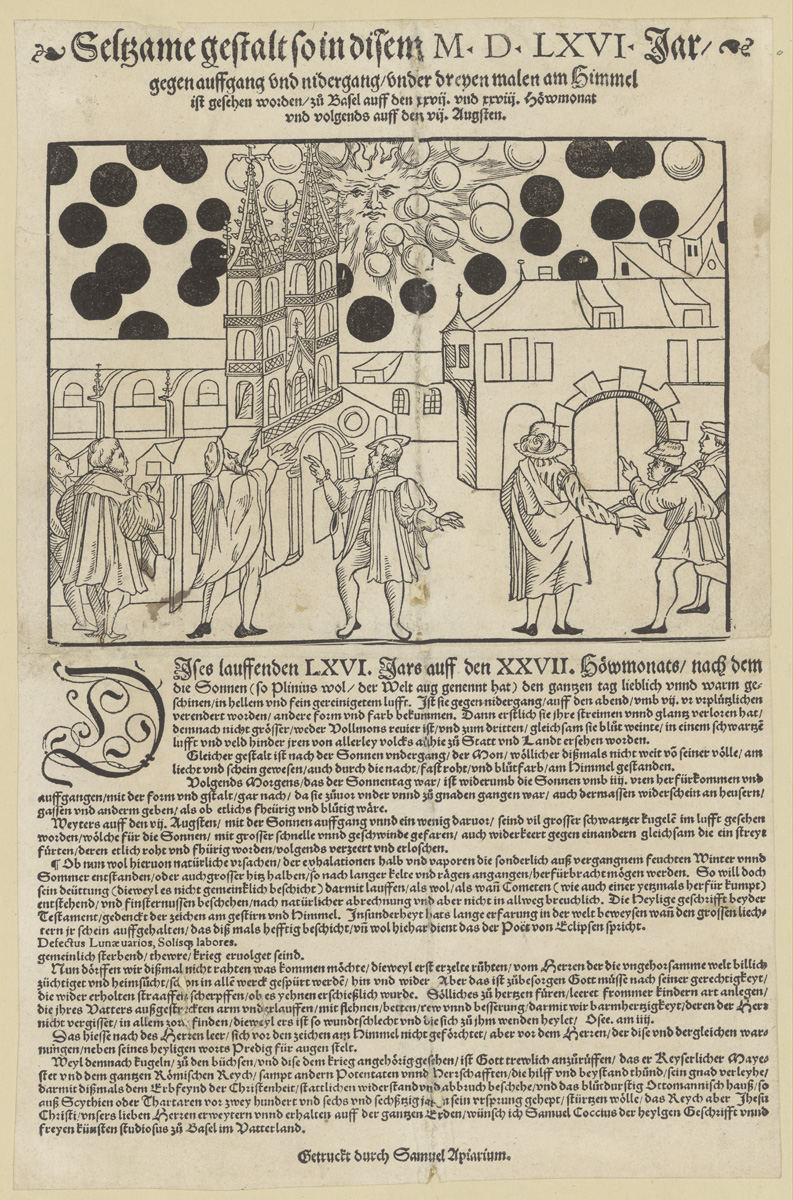

Basel 1566: red and black balls before the sun

A Basel pamphlet reported three episodes in late July and early August 1566: an unusual sunrise, a total lunar eclipse, and a morning when black spheres appeared before the sun, some turning red as if in combat. The leaflet, reflected in the Wickiana collection and discussed by Swiss museum historians, is a classic of the prodigy genre. Later commentators split on causes, ranging from parhelia to particulate veiling and even low latitude aurora like glows under unusual conditions. What matters for our purpose is the consistent language of spheres, color change, and group behavior before the solar disc.

Description of a striking sunrise and sunset, accompanied by black spheres, which were observed over Basel on July 27/28 and August 7, 1566. (Libraries of the UB Zürich and the ZB Zürich)

Comparative note. Modern UAP profiles include clusters of luminous orbs and group maneuvers. The Basel text mirrors the language of multiplicity and fading, but the coupling to sunrise and the clear solar geometry keep atmospheric optics in the explanatory foreground. Here, the overlap with UAP is descriptive rather than mechanistic. (Encyclopedia Britannica)

Stockholm 1535: the sun dogs that became a civic icon

The painting known as Vädersolstavlan in Stockholm Cathedral records a halo display with prominent sun dogs seen over the city on 20 April 1535. The original is lost, but a faithful seventeenth century copy hangs in the Storkyrkan and is widely recognized as an early depiction of a complex halo. Physics based resources explain the parhelia and parhelic circle that produce such scenes, and museum texts situate the work in Reformation politics and civic identity. The painting reminds us that even dramatic sky displays with rings, arcs, and multiple bright “suns” can be fully natural and yet interpreted as signs. (Wikipedia)

The great aurorae of March 1582: low latitude luminous curtains

Recent historical space weather studies have assembled Iberian eyewitness accounts of intense red glows and moving lights over Lisbon and other locations in March 1582, visible over several nights. The descriptions match strong auroral activity and are analyzed alongside European and East Asian records. This case matters for UAP comparison because it shows how pre industrial observers described vivid night lights that moved, waved, and changed color, without invoking discrete craft. The aurora language is a template for diffuse luminous phenomena that can otherwise be misread. (SWSC Journal)

Sailors, St. Elmo’s fire, and the rhetoric of agency

Mariners’ oral culture often framed luminous weather phenomena as visitations or guardians. Antonio Pigafetta’s account of the Magellan voyage describes lights on the masts during storms, including a scene where St. Elmo stood for more than two hours on the mainmast like a flame. The same relation reports multiple saint lights appearing on different masts. Modern atmospheric electricity identifies St. Elmo’s fire as a corona discharge in strong electric fields, and even in modern aviation it remains a striking sight. Pigafetta’s narrative shows how oral interpretation invests phenomena with agency while recording a core visual behavior that is physically well understood. (Project Gutenberg)

Nova and cometology: when new stars stayed put and comets moved

Beyond prodigies, Renaissance observers measured. Tycho’s De nova stella on the 1572 “new star” provided careful positions and brightness estimates for a stationary luminous point that slowly faded. His later work on the 1577 comet argued, against the old Aristotelian view, that comets traversed the heavens beyond the Moon. These books are preserved in first editions and translations and illustrate how rapidly the era evolved toward quantitative sky science. They also provide a crucial filter. If an object stays fixed among the stars for months, it is a nova or supernova, not a nearby craft. If a spectacular sky body moves with measurable parallax or follows a curved path through constellations over weeks, it is cometary. (Causa Scientia)

Comparative analysis: behaviors and motifs that bridge centuries

a) Multiplicity and swarm behavior

Nuremberg and Basel describe many spheres moving, clashing, and dispersing. Modern UAP catalogs describe events where lights appear to split or merge or move in coordinated groups. The similarity lies in the motif of multiplicity and in reports of interaction rather than in an identical cause. In Renaissance sources the solar geometry and timing point to halos and related phenomena for many cases. In modern datasets the highest interest cases tend to be discrete objects with sensor corroboration. The behavior language nonetheless overlaps.

b) Structured forms near the sun

Crosses, rods, crescents, and a dark spear in the Nuremberg sheet, and balls before the sun in Basel, find ready analogues in the ice halo family. Parhelia, parhelic circles, pillars, and tangent arcs can yield symmetric spots, elongated bars, and ring fragments that a witness might narrate as deliberate forms or motions. This is a powerful counterpoint when older sources speak of shape rich scenes near sunrise. Modern UAP reports generally involve lights at night or objects at altitude where ice halo context is absent, which helps separate categories. (Encyclopedia Britannica)

c) Luminous persistence and sudden change

Ensisheim demonstrates a brief flash followed by a durable stone and a long print afterlife. Tycho’s nova demonstrates month long persistence with gradual color change. The aurorae of 1582 demonstrate hours long curtains that ripple and fade. Modern UAP witnesses often report sudden appearance, hovering, and abrupt departure. The continuity lies in the human focus on onset and offset and in descriptive attention to color and intensity. The difference lies in kinematics and environmental coupling. (Astrophysics Data System)

d) Agency and interpretation

Pigafetta reads mast lights as the presence of saints who disperse darkness. Nuremberg and Basel texts moralize battles in the sky. In modern testimony, observers sometimes attribute intention to lights that pace or surround them. In both eras, agency is a narrative overlay on top of a visual event. UAP research benefits when it separates the behavior claim from the interpretive frame while still respecting the witness. (Project Gutenberg)

e) Spheres and globes

The Renaissance record loves the word “globes” or balls. Modern UAP summaries note many reports of luminous or matte spheres. But not all balls are anomalous. Ball lightning has a long and complex literature, with plausible laboratory supported models and thousands of collected accounts. Historical reports of spherical, floating lights during storms fit this class. This does not rule out a residual category. It narrows the field with a well attested natural class. (Nature)

Counterpoints anchored in early modern science and modern physics

Atmospheric optics.

The ice halo family explains multiple bright spots, bars, rings, and pillars near the sun or moon, especially around sunrise and sunset. Parhelia occur at about 22 degrees from the sun when plate shaped ice crystals refract light. The parhelic circle can appear as a white band at the solar elevation, and tangent arcs produce wing like shapes. These models fit events like Stockholm 1535 exactly and provide a strong prior for sunrise centered prodigy reports, including Nuremberg and Basel. (Encyclopedia Britannica)

Space weather.

The 1582 Iberian aurorae are a reminder that the night sky can glow and move in ways that invite agency and alarm. When strong solar storms push aurorae to mid latitudes, long curtains, patches, and red glows can be seen for hours, mimicking some features of long duration UAP light displays while lacking structured objectness. Historical reconstruction of solar activity in March 1582 anchors the case. (SWSC Journal)

Electrical phenomena at sea and on land.

St. Elmo’s fire is a reproducible corona discharge on masts and spars, long integrated into mariners’ lore. Ball lightning remains less well understood, but mainstream models exist. A Nature paper proposes that normal lightning striking soil can loft silicon rich nanoparticles whose oxidation sustains a glowing sphere. National meteorological societies summarize the state of research and caution that ball lightning is rare yet properly attested. These mechanisms explain a subset of glowing orbs that move little and appear during storms. (Wikipedia)

Print culture incentives.

Pamphlets were the first mass media in much of Europe. Illustrated prodigies sold, and moralized explanations came bundled with eye catching images. The Wickiana shows how collectors curated such sheets as an archive of signs. This does not make the events fictive, but it skews the sample toward the spectacular and the meaningful. Analysts should expect selection effects and stylization. (Swiss History Blog)

Measurement and the new astronomy.

By the 1570s and 1580s, observers like Tycho were placing sky events within a measured framework. Comets were tracked against star fields and found to be supralunar. New stars were fixed among the constellations and faded. When a Renaissance report offers positions, durations, and comparisons with bright planets, it is often already moving into the domain of natural phenomena. The more a report looks like a prodigy leaflet, the more it requires optical and cultural filters before being used in any cumulative UAP analysis. (Cambridge Digital Library)

Where the overlaps with modern UAP are real and where they are not

Real overlaps in description

• Multiplicity of lights that appear to interact and then vanish.

• Reports of spherical or circular forms, sometimes with apparent color change.

• Sudden onset and abrupt disappearance.

These are features emphasized in modern UAP witness narratives and acknowledged in official summaries as part of the behavior space of unresolved cases. They are also common in natural sky events that impressed Renaissance eyes. (Director of National Intelligence)

Less persuasive overlaps in kinematics

Modern high interest UAP incidents revolve around unusual kinematics and signature management, including rapid accelerations, instant stops, and movements inconsistent with aerodynamic surfaces or known propulsion. Renaissance prodigy sheets seldom provide granular kinematics beyond verbs like fly, clash, or fall. Where speed or vector change is implied, optical phenomena and the low solar geometry are usually better fits. (NASA Science)

Category caution

When a Renaissance report ties the display to sunrise or sunset and places forms “out of the sun,” ice halos and parhelia deserve priority. When a report unfolds over many nights with broad glows and rippling motion, aurorae deserve priority. When a luminous sphere appears during a storm and near ground level, corona discharge or ball lightning are candidates. A small residual category of short, structured, non solar, non storm, non auroral night lights might remain. Those are the entries most worthy of fresh philological work and environmental cross checks. (Encyclopedia Britannica)

A method to bring Renaissance material into present UAP research

- Corpus building with provenance. Digitize broadsheets, pamphlets, city chronicles, sailor logs, and travelers’ letters, with metadata for place, time, printer, and collection. The Wickiana record provides a starting model for how to structure a prodigy corpus. (Wikipedia)

- Behavior coding. For each report, code whether the phenomenon is point like or diffuse, single or multiple, near solar or nocturnal, and whether sound, color, duration, and environmental conditions are recorded. Use Tycho class events as calibration anchors. (Cambridge Digital Library)

- Environmental pairing. For dated events, check reconstructions of solar activity and geomagnetic indices for aurora candidates, and seasonal weather patterns for halo likelihood. For sea narratives, tag storms and lightning for electrical phenomena. The 1582 aurora case sets the standard here. (SWSC Journal)

- Modern baseline mapping. Align the coded Renaissance behaviors with categories used in official UAP reporting, especially unusual kinematics and signature management, but keep strict fidelity to what the early modern text actually says. Do not silently import present day categories into sixteenth century sentences. (Director of National Intelligence)

- Iconography control. When a woodcut shows rods, crosses, spears, or globes, record both the image and the text. Distinguish emblematic symbolism from descriptive content. Compare depictions of confirmed halos, such as Stockholm 1535, to refine the iconographic sieve for other sheets. (Wikipedia)

Conclusion

Renaissance Europe left us a sky archive both exuberant and disciplined. On one side stand broadsheets and pamphlets that translated startling dawn and dusk displays into battles of spheres and rods, framed as signs in a moral cosmos. On the other stand observers who measured new stars and comets with enough care to reshape the architecture of the heavens. In the maritime world, sailors narrated mast top flames as saintly presences while recording their luminous behavior with a specificity that modern atmospheric electricity can explain.

For UAP studies, the lesson is neither to dismiss the past as credulous nor to recruit it uncritically to modern claims. The broadsheets and paintings are a rich descriptive resource, but their strongest overlap with modern UAP is in visual motifs and group behaviors, not in the extraordinary kinematics that define many unresolved cases today. The counterpoints are strong and internal to the period itself. Optical physics of halos and pillars perfectly fits many sunrise prodigies. Space weather explains long nocturnal glows. Electrical phenomena account for some near field balls of light. The new astronomy of Tycho and his successors already established disciplined classification.

What remains is a small residual class of reports that do not obviously fit halos, aurorae, meteors, or electrical weather and that are not dominated by emblematic rhetoric. These deserve renewed philological attention, environmental correlation, and comparison with modern baselines that value calibrated data. If UAP research is to be global and diachronic, the Renaissance sky is not an embarrassment. It is a training ground that teaches humility about genre and enthusiasm for careful description. (Cambridge Digital Library)

References

• Rowland, I. D. “A contemporary account of the Ensisheim meteorite, 1492.” Meteoritics 25, 1990; ADS full text and Wiley abstract. (Astrophysics Data System)

• Nuremberg 1561: Hans Glaser broadsheet and analysis in Public Domain Review. (Wikipedia)

• Basel 1566: Swiss National Museum blog and background; Basel pamphlet overview. (Swiss History Blog)

• Vädersolstavlan sun dog painting: Wikipedia overview and museum context; Atmospheric Optics resources. (Wikipedia)

• Aurora of March 1582: Journal of Space Weather and Space Climate study and references. (SWSC Journal)

• Pigafetta, First Voyage around the World (Hakluyt Society translation, Project Gutenberg): St. Elmo’s fire descriptions. (Project Gutenberg)

• Tycho Brahe: De nova stella English translation and comet treatise context in Cambridge University Digital Library. (Causa Scientia)

• Atmospheric optics: Britannica entry on sun dogs; WMO Cloud Atlas entry on parhelic circle. (Encyclopedia Britannica)

• Ball lightning: Nature 403 paper by Abrahamson and Dinniss; Royal Meteorological Society summaries. (Nature)

• Modern UAP baselines: ODNI Preliminary Assessment 2021; NASA UAP Independent Study Team Report 2023; AARO Historical Record Report 2024. (Director of National Intelligence)

Claims Taxonomy

Verified

• The Ensisheim meteorite fell on 7 November 1492 and generated immediate broadsheets by Sebastian Brant. Surviving contemporary descriptions and the preserved stone confirm the event. (Astrophysics Data System)

• The Nuremberg broadsheet of 1561 by Hans Glaser exists and describes a morning display of spheres, rods, and a large dark object, now in the Zentralbibliothek Zürich collection. (Wikipedia)

• The Basel pamphlet of 1566 reports red and black balls before the sun on several mornings, and is part of the Wickiana type print culture. (Wikipedia)

• The Stockholm painting Vädersolstavlan records a complex halo display with sun dogs over the city in 1535. (Wikipedia)

• Iberian eyewitness accounts describe intense low latitude aurora in March 1582 across several nights. (SWSC Journal)

• Pigafetta’s Magellan narrative records St. Elmo’s fire as prolonged mast top lights during storms. (Project Gutenberg)

• Tycho’s De nova stella and his comet studies provide measured frameworks for new stars and the 1577 comet. (Causa Scientia)

• Modern public baselines by ODNI, NASA, and AARO emphasize standardized data and a subset of incidents with unusual kinematics. (Director of National Intelligence)

Probable

• Many sunrise prodigy reports with shapes “out of the sun” are best explained by ice halos, including parhelia and parhelic circles, which can generate globes and bars that appear to move or clash. (Encyclopedia Britannica)

• A subset of spherical lights in storm contexts correspond to ball lightning or corona discharges. (Nature)

Disputed

• Readings that treat the 1561 and 1566 broadsheets as literal accounts of anomalous craft in combat. The timing, solar geometry, and genre favor atmospheric optics and rhetorical framing. (Wikipedia)

Legend

• Pamphlet portrayals of sky battles as providential warnings belong to a didactic tradition in which meaning precedes measurement. (Swiss History Blog)

Misidentification

• Interpreting complex halo displays like Stockholm 1535 as structured vehicles rather than atmospheric optics. (Wikipedia)

Speculation labels

Hypothesis

A small residual set of Renaissance night time reports that lack solar coupling and storm context may represent a continuity of rare luminous events whose behavior space partly overlaps with the modern UAP profile. Demonstration requires behavior coding and environmental controls.

Witness Interpretation

At sea, St. Elmo’s fire and other lights were narrated through the language of saints. On land, broadsheets framed halos and glows as moral portents. Agency attributions are interpretive overlays on visual behavior. (Project Gutenberg)

Researcher Opinion

A digitized, provenance rich corpus of Renaissance sky reports, stratified by environment and genre, and mapped to modern UAP baselines would sharpen both debunking and discovery. It would reduce false positives from halos and aurorae and isolate the few reports that genuinely resist known classes. (Director of National Intelligence)

SEO keywords

Renaissance prodigies and UAP, 1561 Nuremberg broadsheet spheres rods, 1566 Basel celestial pamphlet red black balls, Ensisheim meteorite 1492 Sebastian Brant broadsheets, Stockholm sun dog painting Vädersolstavlan, 1582 Iberian aurora historical space weather, Pigafetta St. Elmo’s fire Magellan, Tycho Brahe De nova stella 1572 comet 1577, ice halos parhelia parhelic circle history, atmospheric optics and early modern prodigies, Wickiana broadsheets Zurich, comparative UAP characteristics behaviors, ODNI NASA AARO UAP reports.