Across two sultry July weekends in 1952, Washington D.C.’s skies and radar scopes “lit up.” Controllers at Washington National Airport (today’s Reagan National), the city’s Air Route Traffic Control Center (ARTC), and Andrews AFB reported clusters of unknown targets, sometimes coincident with pilot and tower visual sightings, over the nation’s capital. Interceptors were scrambled; the news cycle went into overdrive; and the U.S. Air Force convened what contemporaries called its largest press conference since World War II. The events compressed technical puzzles (radar physics in temperature inversions), national-security anxieties (restricted airspace over the White House and Capitol), and a new public lexicon –“flying saucers” – into one of the most influential UAP episodes in U.S. history. (The Washington Post)

What happened: a chronology

Weekend 1 – Saturday night into Sunday morning, July 19-20

- Initial radar detections. At 11:40 p.m., controller Ed Nugent at National Airport saw seven unidentified returns about 15 miles SSW of the city. Harry G. Barnes, the senior controller, verified the contacts; the airport tower (controllers Joe Zacko and Howard Cocklin) also reported unknown blips and a bright object visually that departed at high speed. Multiple radar sectors populated with unknowns that at times moved over central D.C., prompting calls to Andrews AFB.

- Airliner and tower visuals matched to radar. Capital Airlines captain S.C. “Casey” Pierman (Flight 807) reported six “falling-star-without-tails”-type lights during a 14-minute interval while controllers reported coincident pips near his position.

- Interceptor response and disappearances. Two F-94 interceptors from New Castle AFB (Delaware) were scrambled after 3 a.m.; as they arrived over D.C., the unknowns faded from National’s scopes – then returned when the jets departed. The returns lapsed around sunrise. (The Washington Post)

Week of July 21–25

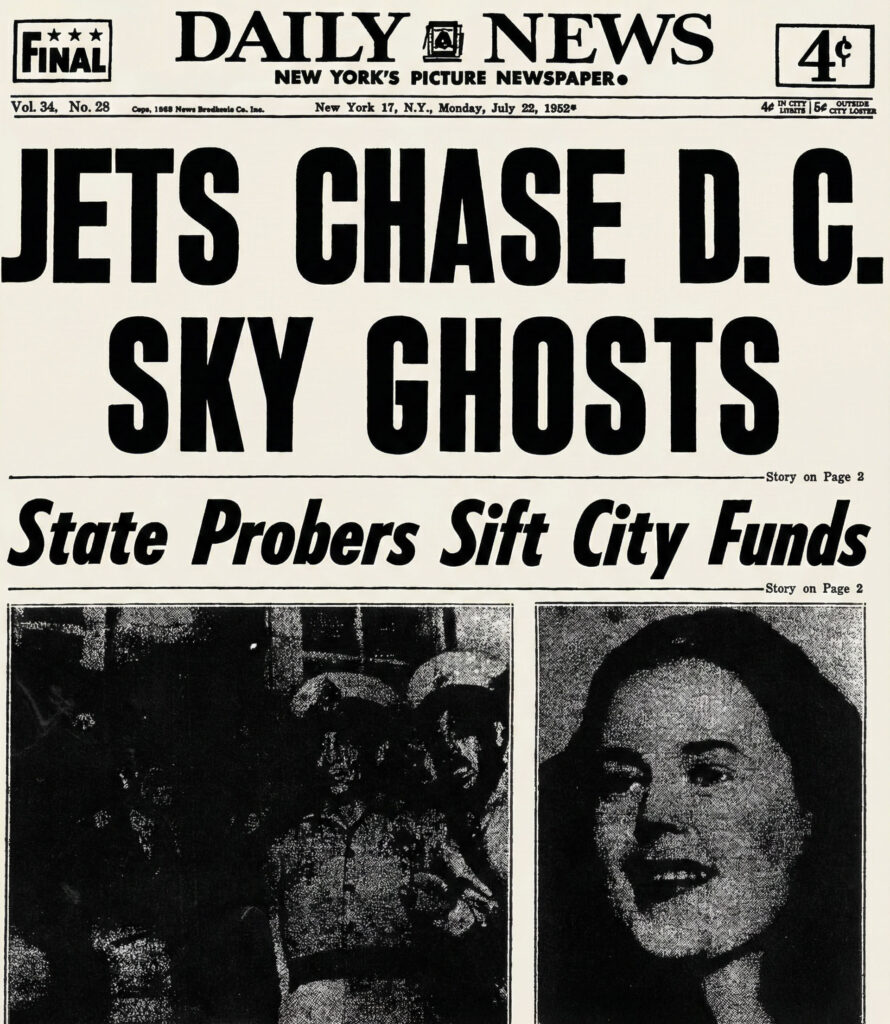

- Coverage and concern. Headlines such as “Radar Spots Air Mystery Objects Here” and “Saucers Swarm Over Capital” ran nationwide. Within the government, the question of how to respond quickly dominated. (The Washington Post)

Weekend 2 – Saturday night into Sunday morning, July 26-27

- Renewed radar-visual activity. Shortly after 8 p.m., National Airport’s ARTC and tower radars, and Andrews AFB radar, again tracked unknowns. A Project Blue Book liaison (Maj. Dewey Fournet) and a Navy radar specialist (Lt. John Holcomb) arrived to observe. Reports included multiple glowing lights coincident with radar pips. Controllers also requested an Air Force B-25 fly through a target area; nothing anomalous was seen at one vector, underscoring the mixed character of the night’s returns. (The Washington Post)

- Jet chases. Interceptors returned after 11 p.m. One pilot (Lt. William Patterson) reported several strange lights and attempted a chase but could not close. Again, returns intermittently faded with combat air patrol presence and reappeared afterwards. (The Washington Post)

The Pentagon responds – July 29

- White House interest. President Truman asked his Air Force aide, Brig. Gen. Robert Landry, to obtain an explanation. That morning Landry spoke with Project Blue Book’s director Capt. Edward J. Ruppelt, who floated an inversion-related radar-propagation possibility but said the case was not yet investigated. The CIA’s own historian later noted the agency’s July 1952 concern and subsequent review of the surge in reports. (The Washington Post)

- The Samford press conference. Maj. Gen. John A. Samford (USAF Director of Intelligence) and colleagues briefed reporters. Samford’s carefully hedged remarks left the door open, “a certain percentage…from credible observers of relatively incredible things”, but the press seized on “temperature inversion” as a leading explanation for the radar blips. Ruppelt later wrote this was the largest and longest Air Force press conference since WWII, and that the twin National sightings were still carried as unknowns within Blue Book files at that time. (Project Gutenberg)

- Immediate effect. Press attention cooled and the flow of reports dropped from ~50 per day to ~10 per day within a week, according to Ruppelt. (Project Gutenberg)

Inside the radar rooms: equipment, environment, and what “multi-sensor” meant in 1952

A key to understanding the Washington flap is appreciating who was looking with what.

- Two civil radars, one military. The Washington ARTC Center operated a Microwave Early Warning (MEW) radar; the airport tower used an ASR-1 airport-surveillance radar; Andrews AFB had its own search radar. The Civil Aeronautics Administration (CAA) cataloged the differences: the MEW had higher peak and average power and a higher elevation angle, producing more hits per scan than the ASR-1. That asymmetry helps explain why the Center saw more unidentified targets than the tower.

- Weather was not ordinary. The CAA’s Technical Development Report No. 180 (May 1953) correlated Washington ARTC logs with U.S. Weather Bureau records and found a temperature inversion was indicated in almost every instance when unidentified radar targets or visual objects were reported in the Washington area. The report reconstructed the persistent Bermuda High heat-wave pattern that month and noted low lightning and low atmospheric electrification conditions often conducive to anomalous propagation of radio waves.

- How inversion can spoof radar (and the “double-speed” clue). Investigators tracked ~80 unidentified targets on the Washington MEW and later at Indianapolis (ASR-2) during inversion events. Kinematic analysis showed many targets’ apparent motions lined up with winds aloft if you halved their apparent velocities, consistent with an atmospheric “lens” effect refracting the radar beam to ground and back. The report explicitly argued that earlier claims of “sudden accelerations to supersonic speed” were likely controller identity transfers between fading and appearing refractive targets, not true accelerations of solid craft.

- But not everything on the scopes was “weather.” The same CAA analysis cautioned against assuming all slow-moving unidentified targets are refractive artifacts; small helicopters and other returns can look similar. This was, and remains, the analyst’s dilemma when weather clutter and real traffic coexist.

In short, Washington had real airplanes, atmospheric radar angels, and possible unknowns on the scopes at the same time. Disentangling them in real-time, especially in 1952 with analog displays, was hard.

Radar-visual claims: what lines up, what doesn’t

Convergences that matter:

- Temporal covariance of radar and visual reports on both weekends, including from tower personnel and airline crews, is well established in contemporary press accounts and in Blue Book-era summaries. Controllers described bright, maneuvering lights that coincided with radar pips near their aircraft or reference points. (The Washington Post)

- Cross-facility awareness. At various points National’s ARTC, National’s tower, and Andrews AFB were all tracking unknowns; at least once the disappearance of a target was reportedly simultaneous across scopes and visually, according to later scientific critiques. (UAP researchers debated the robustness of that “simultaneity” claim; this is a recurring point of contention.) (kirkmcd.princeton.edu)

Complications and contradictions:

- Targets faded on interceptor arrival. Both weekends, the unknowns tended to disappear as F-94s reached the area, then reappear when the jets returned to base or moved away. This could signal adaptive behavior by intelligent craft – or consistent with beam-path geometry changes as fighter altitude and radar look angles shifted, reducing anomalous propagation. The data support both interpretations. (The Washington Post)

- Apparent extreme speeds. Contemporary accounts sometimes cited radar-calculated speeds in the thousands of mph. The CAA’s reconstruction strongly suggests many of those “bursts” were artifacts of track swaps under refractive conditions rather than true accelerations. This doesn’t falsify every radar-visual in the flap, but it counsels caution about the most dramatic kinematic claims.

Witness testimony: controllers, pilots, and what they said

- Harry G. Barnes (senior controller) later wrote that the unknowns maneuvered in helter-skelter fashion and appeared to play “cat-and-mouse” with interceptors; Ed Nugent provided the initial radar detection; Joe Zacko and Howard Cocklin saw a bright light out the tower window simultaneous with a radar target. Decades later, Cocklin told The Washington Post he was still convinced he saw an object “on the screen and out the window.”

- Capt. S.C. “Casey” Pierman (Capital 807) reported six fast-moving lights over ~14 minutes while in radio contact with the tower that confirmed proximate radar pips.

- Lt. William Patterson (F-94) reported multiple lights he could not overtake. The combination of pilot visuals and ground returns during this period is a core reason the case has remained a touchstone among radar-visual UAP proponents. (The Washington Post)

Press coverage: from banner headlines to “hot air”

The press frenzy began immediately after weekend one and exploded after weekend two, with front-page headlines across the country and a wave of rumor-control stories. The July 29 Air Force press conference, led by Gen. Samford, emphasized that many sightings had ordinary explanations while acknowledging “a certain percentage” of credible but puzzling reports. Reporters quickly distilled the event to a “temperature inversion” narrative, “Washington’s famous hot air”, and the public temperature subsided. Ruppelt’s memoir notes that reports fell by ~80% within a week, illustrating how official tone shapes reporting behavior. (The Washington Post)

Official and scientific re-analyses: an evolving picture

1) Civil Aeronautics Administration (1953)

The Technical Development and Evaluation Center at Indianapolis issued Technical Development Report No. 180, “A Preliminary Study of Unidentified Targets Observed on Air Traffic Control Radars.” Using ARTC logs, Weather Bureau data, and controlled observations, the CAA concluded that many unidentified targets during the Washington period were “secondary” refractive returns produced near inversion levels – and that inversion conditions correlated strongly with both radar targets and reports of “flying saucers.” The study proposed a physical model (moving refractive “eddies” acting as atmospheric lenses) that explained the observed “double-speed” effect and the alignment of apparent target velocity with winds aloft.

2) Air Force / CIA response (1952–1953): the Samford briefing and the Robertson Panel

- Samford briefing (July 29, 1952). This event publicly advanced inversion as a likely contributor in D.C., while also framing the overall UAP problem as largely non-threatening to national security. (Project Gutenberg)

- CIA’s Scientific Advisory Panel (the Robertson Panel, January 1953). Reviewing “significant” cases from 1952 (including Washington), the Panel found no evidence of a direct threat and recommended an interagency educational program with two explicit aims: training (improving visual/radar recognition) and “debunking” to reduce public susceptibility and prevent channel saturation that could mask real threats. The minutes are blunt: reduce the aura of mystery and strip UAP of special status; use mass media and training films to that end. (The Black Vault)

3) The Condon Study (1968)

The University of Colorado report’s radar chapter cited the CAA study as “an excellent analysis” of the probable radar situation in July 1952 and appended meteorological summaries for the Washington weekends. In brief: the Condon team viewed temperature structure as centrally relevant and did not reopen the case as an enduring unknown. (files.ncas.org)

4) Dissenting scientific voices (1960s–2000s)

- Edward J. Ruppelt emphasized that the twin National sightings remained “unknowns” in Blue Book at the time of the press conference and argued that simplistic label-and-dismiss approaches were inadequate for strong radar-visuals. (Project Gutenberg)

- James E. McDonald (atmospheric physicist) criticized catch-all “anomalous propagation” explanations, arguing that several radar-visual cases (often citing Washington as exemplar) retained puzzling multi-sensor features not easily erased by meteorology alone.

- Bruce Maccabee (optical physicist, U.S. Navy) independently reviewed Washington materials and concluded that solid, non-conventional objects likely flew over D.C. a judgment he shared publicly on the case’s 50th anniversary. (The Washington Post)

Air-traffic and national-security context

Washington’s flap unfolded amid heavy but tightly managed airspace, with civil CAA and military ADC radars operating in parallel and restricted areas over the federal core. The flare-up accelerated coordination between civil and military radar planning and, in the immediate term, ensured interceptors were on faster alert for capital-region scrambles. (More broadly, the CIA’s own history credits the 1952 surge with catalyzing formal interagency monitoring and the 1953 scientific panel.) (CIA)

The operational lesson recorded by the CAA was pragmatic: spurious inversion-related returns can seriously complicate traffic control, and procedures/training should help controllers distinguish weather effects from aircraft. That lesson influenced air-traffic training doctrines and later hardware (e.g., better clutter suppression and processing).

What is known versus what remains contested

What is well-documented

- Two weekend surges (July 19–20; July 26–27) of radar tracks and visuals in the Washington area, with interceptor scrambles, are firmly established from controller logs, military records, and contemporary press. The Samford press conference and White House interest are a matter of record. (The Washington Post)

- Meteorological inversions were present during key windows, and a CAA technical study (1953) articulated a physically plausible mechanism that can produce small, moving radar targets that line up with winds aloft and mimic motion -including “apparent” rapid shifts via identity swaps.

What is contested

- The extent to which inversion explains all of the radar-visuals those nights is disputed. Blue Book’s immediate post-incident stance left the twin National sightings as unknowns, even as public messaging emphasized inversions. Later Condon/RAND-era treatments leaned toward meteorology; McDonald and others pressed that the multi-sensor correlations and pilot/ground concurrency in several sequences deserved continued “unknown” status pending better data. (Project Gutenberg)

- Kinematic extremes. Claims of “thousands of mph” maneuvers are not reliably established after the CAA reconstruction; many such figures are almost certainly analysis artifacts under refractive conditions. That said, pilot reports of persistent lights impossible to overtake at then available jet speeds remain part of the record.

How UAP researchers interpret Washington today

- Hypothesis (physics-first): Anomalous propagation + mixed traffic. The bulk of radar anomalies were temperature-inversion “angels” superposed on normal air traffic and occasional balloon/bird returns; some visual reports track astronomical objects distorted by refraction. (This is the CAA/Condon frame.)

- Researcher Opinion (minority scientific view): Non-conventional objects among the clutter. The inversion model explains a lot but not all: specific time-locked radar-visual coincidences and pilot accounts still imply structured objects under control, at least in part of the dataset. (See Ruppelt’s “unknowns” remark and McDonald/Maccabee assessments.) (Project Gutenberg)

- Witness Interpretation: Controllers and pilots often described the unknowns reacting to jets and “monitoring” radio traffic (disappearing on arrival, reappearing on departure). Whether that is intelligent behavior or a selection bias created by changing look angles and refractive paths is unresolved. (The Washington Post)

Bottom line

The Washington D.C. UAP flap is both a cautionary tale about atmospheric radar artifacts and a persistent puzzle because credible multi-sensor sequences and converging testimony remain in the record. The official trajectory, Samford press conference → CAA inversion study → Robertson Panel’s training/debunking program → Condon’s endorsement of the inversion analysis – shaped U.S. policy for years. Yet, even from within Blue Book’s leadership at the time, we have a reminder that the twin National sightings were still carried as “unknowns.” In UAP research terms: Washington 1952 is not a solved riddle; it is the benchmark case that taught investigators to respect both radar physics and the stubborn residue of correlated observations that refuse easy categorization. (Project Gutenberg)

References

- Civil Aeronautics Administration, A Preliminary Study of Unidentified Targets Observed on Air Traffic Control Radars (Technical Development Report No. 180), Indianapolis, May 1953. (Covers Washington and Indianapolis observations; inversion correlation; MEW vs. ASR-1 details.)

- Maj. Gen. John A. Samford, Pentagon press conference statements and minutes (July 29–31, 1952). (National Archives short film; transcript.) (DocsTeach)

- Edward J. Ruppelt, The Report on Unidentified Flying Objects (1956). (Blue Book director’s narrative on the D.C. sightings, press conference scale, and classification as “unknowns.”) (Project Gutenberg)

- CIA Scientific Advisory Panel on Unidentified Flying Objects (Robertson Panel), January 1953. (Findings: no direct threat; recommends training and “debunking” program to reduce channel saturation and public susceptibility.) (The Black Vault)

- Condon Committee, Scientific Study of Unidentified Flying Objects (1968). (Radar chapter endorsing the 1953 CAA analysis; Appendix L on July 1952 Washington weather.) (files.ncas.org)

- The Washington Post (Peter Carlson), “50 Years Ago, Unidentified Flying Objects…Seized the Capital’s Imagination,” July 21, 2002. (Contemporary reconstructions; quotes from controllers; Pierman; press dynamics.) (The Washington Post)

- CIA Center for the Study of Intelligence, Gerald K. Haines, “The CIA’s Role in the Study of UFOs, 1947–90” (1997). (Context for 1952 surge, interagency interest leading to Robertson Panel.) (CIA)

- James E. McDonald, statements and papers critiquing anomalous-propagation catch-alls in radar-visuals (citing Washington as exemplar).

Claims Taxonomy

Verified:

- The two July 1952 radar-visual weekends in Washington D.C., interceptor scrambles, and the July 29 Pentagon press conference. (The Washington Post)

- Presence of temperature inversions and the existence/content of CAA TDR #180 (1953) analyzing Washington radar anomalies.

- CIA-sponsored Robertson Panel conclusions on training and “debunking” as policy aims. (The Black Vault)

Probable:

- A substantial fraction of radar anomalies those nights were anomalous-propagation artifacts under inversion (CAA’s technical assessment, aligned with later Condon chapter).

Disputed:

- Whether all key radar-visual correlations can be dismissed by inversion and identity-swap artifacts; whether at least some targets represented structured, non-conventional objects. (Ruppelt’s “unknowns,” McDonald’s critique, Maccabee’s pro-object reading vs. Condon/CAA.) (Project Gutenberg)

Legend:

- Newspaper embellishments (e.g., dramatic absolute speeds, omnidirectional “swarms” at fantastical rates) not supported by instrumental re-analysis.

Misidentification:

- Specific coincident reports later shown to be non-anomalous (e.g., a B-25 over the Potomac vectoring through a radar target without visual confirmation; routine aircraft and weather echoes inside clutter). (The Washington Post)

Speculation labels

Hypothesis: A mixed field, real aircraft + inversion-driven angels – produced confusing tracks; some radar-visual coincidences still indicate structured, non-conventional objects.

Witness Interpretation: “The UAPs reacted to jets and monitored radio traffic” (explanations range from intelligent maneuvering to changes in refractive beam geometry producing fades on intercept).

Researcher Opinion: McDonald/Maccabee argue for non-conventional objects amid clutter; CAA/Condon argue inversion physics plus misidentifications explain the dataset’s bulk.

SEO keywords

Washington D.C. UAP flap 1952, Washington National radar sightings, Andrews AFB radar, temperature inversion anomalous propagation, Samford press conference 1952, Robertson Panel debunking, radar-visual UAP, S.C. Casey Pierman testimony, Harry G. Barnes controller, Project Blue Book unknowns, CAA Technical Development Report 180, Condon Report Washington 1952.

Origin and Ingestion Date